Yarns & Photos

We have found in storage the last few boxes of the original 1992 print. This book has not been re-released. These won't last long!

$149 + Postage

Buy Now

Yarns & Photos

We have found in storage the last few boxes of the original 1992 print. This book has not been re-released. These won't last long!

$149 + Postage

Buy Now

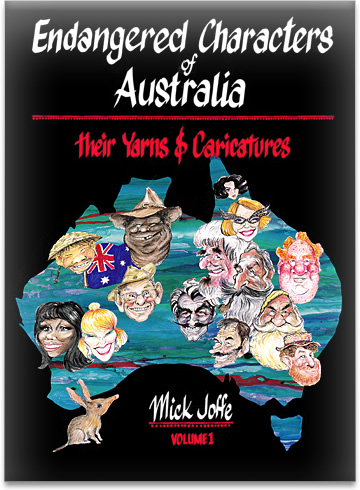

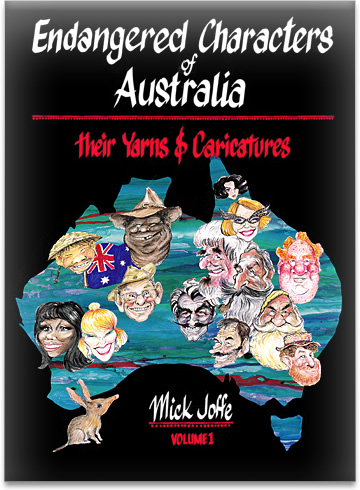

Endandgered Characters of Australia

We have found in storage the last few boxes of the original 1995 print. This book has not been re-released. These won't last long!

$149 + Postage

Buy Now

Endandgered Characters of Australia

We have found in storage the last few boxes of the original 1995 print. This book has not been re-released. These won't last long!

$149 + Postage

Buy Now

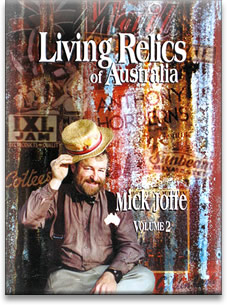

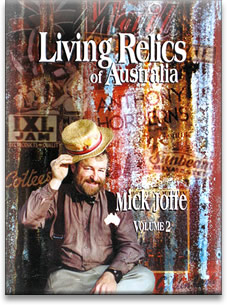

Living Relics of Australia

Living relics contains 25 of our greatest living characters. This coffee table hard-cover book combines the very Australian art of caricature with oral history - the history of drovers, shearers, naturalists, miners, artists, explorers, etc. Their caricature captures them on the outside and their own words capture them on the inside.

Only $29 + Postage

Buy Now

Living Relics of Australia

Living relics contains 25 of our greatest living characters. This coffee table hard-cover book combines the very Australian art of caricature with oral history - the history of drovers, shearers, naturalists, miners, artists, explorers, etc. Their caricature captures them on the outside and their own words capture them on the inside.

Only $29 + Postage

Buy Now

Interviewed: 1993

Published online: Friday, 1 January 2010

This interview is from Endangered Characters of Australia.

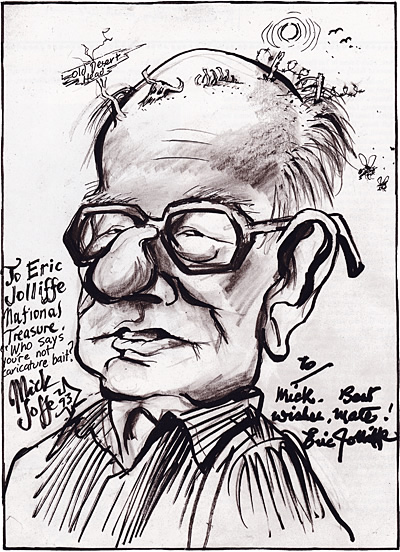

Eric Jolliffe

1907 - 2001

Famous cartoonist of the outback

I was born in 1907 in England. I came out with my family when 4 years of age. There were 13 of us all told. I’m the last of them. ‘Jolif’ was the early English spelling of ‘jolly’.

I belonged to the first Black and White Artists Club during the 1930s. We included the Smiths Weekly and Bulletin artists. There was Willy Web, George Aria, Sprod, Jack Lesby, Les Such, Jim Russell, Les Dixon and Joe Johnson.

In those days I started by submitting cartoons to the Bulleting. Ted Schofield was Art Director and John Frith was caricaturist and gag man. The manager of the Bulletin sat in and the 3 of them selected the cartoons. My first one was a pretty lousy sort of gag... a couple spooning on a lounge... a 2-liner gag as they used in those days. She’s got her head on his chest and she says, “I can hear something throbbing,” and he says, “Yeah, it’s me bunion.”... corny, but the Bulletin was like that. If someone was submitting for a long time and he came up with something reasonable, they would buy it... may not even use it... but to give him encouragement or a feed and it was part of their policy. I didn’t know of any other publisher like it. It’s a rougher world now... a more competitive world... but in those days the world was full of readers. Now few people read to any extent. They scan or read shorties. You see, first it was radio, now it’s television and radio. They are both so professional that people simply haven’t got time to read. Their favourite programmes and news happen while they are peeling the spuds.

The Smiths Weekly after the war was one of the only 2 jobs I’ve ever had as a staff member. The other one was the ABC Weekly. So all my life I’ve been a freelancer ‘cause I was mostly interested in the Outback and I didn’t want to be tied down with anything else.

I first got to know the Aborigines during the war when I was in the army in the camouflage unit. They found that artists and architects were the best people for camouflage. I was posted extensively around the top end of Australia, camouflaging airports and installations and I worked a lot with the Aborigines and I learnt to have a lot of respect for them. This was before the grog got into these areas and degraded their way of life. A white man often learns one thing and slogs away at it for his livelihood. An Aborigine in the bush has to use his brain all the time for survival in his environment and, in using initiative, he gains know-how all the time. They have also lived a nomadic life out of necessity and in so doing have not buggered up the country like the white man. Oh, I think quite a lot of the Aboriginal people.

A couple of bureaucrats reckoned my art was an insult to the Aboriginal race. They just wanted to draw attention to themselves and reckoned to have a piece of me was the way to go. They fell flat on their faces, of course. The drawing they seized on was of a lubra, She was wearing a bra and a couple of lubras in the foreground were saying, “It’s a white man’s garment she got from a missionary’s wife”... but she’s got it on the backside instead of the boobs. They picked that out as the insult to all Aboriginal women and the joke was, I’d just been invited as guest of honour to the Aboriginal Olympic Games in Arnhem Land. It was around 1971 and it was a big deal. All the tribes from the Top End and the big settlements throughout the north got together every year and did everything that was done in the Olympic Games and on top of that was spearing and throwing boomerangs, fire-lighting and so on. So I went and took with me an exhibition of cartoons of Saltbush Bill and Witchetty’s Tribe and right in the middle of them was the cartoon that was supposed to be an insult to all Aborigines and I’ve got a photo of all admiring the cartoons and they steamed in for 4 days. It was a terrific event.

It’s so long since I’ve been up north in the bush, most of my old mates are dead: like Bill Harney, first custodian of Ayres Rock, Ted Morey, Tas Fitzer. Tas was a policeman in the Territory back in the days when things were pretty tough and they lived on horse patrol, existing out of a saddlebag. I used to do a lot of lecturing for adult education in Queensland and a mate talked me into a lecture tour. I used to go up every winter and they’d drive me all through the Queensland Outback and I’d do as many as 70 odd lectures in a tour. I talked about the outback and its people and illustrated it with cartoons and also Aboriginal life illustrated with cartoons. The lectures went down well ‘cause there was a laugh in them. I would give ‘em some facts then whack ‘em with a cartoon ‘cause there wasn’t anything in the bush that I hadn’t done a cartoon of. I included barns, sheds and relics. I’d drawn all through the bush. I’ve had an interesting life.

One day in Cairns a mate of mine, Reg Stocker... he was in charge of Adult Education in Cairns... we were out in the sticks... he said, “I’ve got an idea. While the mob are shuffling in, if I was to put a drawing board on stage and you do a bit of drawing. What do you think?” I said, “I think it’s a lousy idea. What put that in ya head?” He said, “Oh, every winter one or two Eric Jolliffes come through Queensland doing portraits. Frankly you’re the most improbable Eric Jolliffe we’ve ever had in Queensland. You don’t look like an artist, you don’t have a beard, you don’t have velvet pants.” I had no answer to that so I went along with it and set up a drawing board and got hooked on it and would be drawing and have a microphone on my chest, maybe telling funny yarns all the while. So it grew like topsy till it was half of the night’s programme. The audience was fully absorbed. They loved it. Well, then somebody said, “Why don’t you have a crack at Clubland?” It was the 1960s and clubs and poker machines were springing up... OK so I’ll give it a go. I went to a few of the agents. Quick-sketch artists were as dead as a doornail. They wouldn’t have them in the clubs... but I made more money there than I’d ever made drawing. A friend of mine who enjoyed my cartoons put me on and I was away. I was making more as a club entertainer than as a cartoonist.

I’d like to have my wife mentioned [May died 10 days ago] ‘cause she was a great standby and support for 60 odd years and a great manager... terrific person. May was born in Scotland in 1910. I was 25, she was 21 when we married in Sydney. I owe a lot of my career undoubtedly to her. The family were very supportive also. My daughter Margaret is a graphic artist and my grand-daughter Jane is a graphic artist and of course my son-in-law Ken Emerson is a cartoonist. We’re all good mates. We all pull together.

Well, Mick, I think the most important thing in life is to enjoy your work. Enjoy what you’re doing. There’s nothing worse than doing a job your heart’s not in. I’ve done a lot of lousy jobs in my early life. Once I started drawing, life started to have a lot of purpose and meaning to it and no day is ever too long... and just because you do a short day it’s still a long one if it gives you no joy or purpose or sense of fulfilment. You know the poor sods working on the assembly line doing the same job over and over... I always feel for them. My art has supported us well over half a century.

I was with Professor Elkin on an expedition in Arnhem Land just after the war, 1946. I was on 2 National Geographic expeditions to Arnhem land, in 1948 and in 1954. They were a combination of Australian and American scientists studying Aboriginal art and survival. There were groups of different specialists, for example Professor McCarthy from the Australian Museum. I was the artist.

Once I went into a pub in George Street to look at some of my Witchetty Tribe cartoons they’d blown up on the walls. I was having a quiet beer when this young bloke next to me said, “He’s not bad, is he?” I didn’t want to start any trouble so I agreed that the artist wasn’t bad. Then he said, “You know he’s still alive.” Well, I replied, “I can’t tell you how pleased I am to hear that.” When I left I made sure I stayed alive too by looking both ways before crossing the road.

Mick you’re an outgoing character. I think you’ll go well too because of that spectacular vehicle with all the Joffe caricatures on top. When you pull in, everyone will know about it. In the bush they quietly observe. Anyone new in town is checked out and, believe me, you will be checked out. Oh, you’ll do all right.

In 1911 the Jolliffes emigrated from Great Britain to Western Australia. Eric absorbed the literature of Henry Lawson, Banjo Patterson and Steele Rudd and knocked around the Outback for several years. He joined the Black and White Artists Club in the 1930s when they were the heroes of the land and the Smiths Weekly and the Bulletin’s reputations were built upon how good their artists were. During the war Eric was a camouflage officer along the north coast of Australia from Queensland to Western Australia and began his lifelong association with Aborigines. He has spent 50 years recording them and old-time Outback Australia before motor cars and wireless and telephone changed the face and character of our bush (don’t even dream about computers and satellite dishes). In his 135 books, many calendars, newspaper cartoons and paintings, Eric has amassed a great treasury of our horse-drawn bush era of thatched bower sheds, wagons, windmills, horse teams and slab homesteads. He has people them with real Australians of the time in black and white and given them humour and personality. They are portrayed as equal under his brush as they are under the Southern Cross. In 1981 he was awarded the very prestigious Bourke Order of the Outback for services to the people of the Outback. Only 2 other awards of the Bourke Order had been made, one to the Royal Flying Doctor Service and the other to Colleen McCullough. Well, me and a few thousand kinds got in first with the awards ‘cause he was our boyhood idol. He was the single biggest influence on me hitting the road to do this book and the first character I recorded. It was a highlight and an honour. Eric Jolliffe, you’re all right in my Book!

Mick Joffe

More Characters

Since the early 1970s, Mick Joffe's passion has been to caricature and record endangered characters of Australia, and the world. As of 2015, the majority of these interviews exist only in manuscript form.

Click here to see the full list of interviews...

Yarns & Photos

We have found in storage the last few boxes of the original 1992 print. This book has not been re-released. These won't last long!

$149 + Postage

Buy Now

Yarns & Photos

We have found in storage the last few boxes of the original 1992 print. This book has not been re-released. These won't last long!

$149 + Postage

Buy Now

Endandgered Characters of Australia

We have found in storage the last few boxes of the original 1995 print. This book has not been re-released. These won't last long!

$149 + Postage

Buy Now

Endandgered Characters of Australia

We have found in storage the last few boxes of the original 1995 print. This book has not been re-released. These won't last long!

$149 + Postage

Buy Now

Living Relics of Australia

Living relics contains 25 of our greatest living characters. This coffee table hard-cover book combines the very Australian art of caricature with oral history - the history of drovers, shearers, naturalists, miners, artists, explorers, etc. Their caricature captures them on the outside and their own words capture them on the inside.

Only $29 + Postage

Buy Now

Living Relics of Australia

Living relics contains 25 of our greatest living characters. This coffee table hard-cover book combines the very Australian art of caricature with oral history - the history of drovers, shearers, naturalists, miners, artists, explorers, etc. Their caricature captures them on the outside and their own words capture them on the inside.

Only $29 + Postage

Buy Now

Caricature of Eric Jolliffe, by Mick Joffe

Caricature of Eric Jolliffe, by Mick Joffe

Ray Blisset“The Blizzard”

Ray Blisset“The Blizzard” Doc HowlettPioneer tuna fisho of Port Lincoln

Doc HowlettPioneer tuna fisho of Port Lincoln Rod EmmersonRockhampton’s popular cartoonist

Rod EmmersonRockhampton’s popular cartoonist Bob McMawOlest man in Australia, reflections on Queen Victoria

Bob McMawOlest man in Australia, reflections on Queen Victoria Noel FullertonThe Camel King

Noel FullertonThe Camel King Sir Edmund HillaryFirst man to climb Mount Everest

Sir Edmund HillaryFirst man to climb Mount Everest