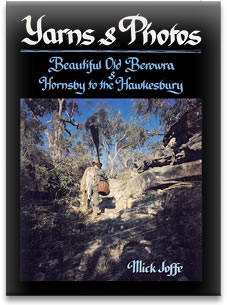

Yarns & Photos

We have found in storage the last few boxes of the original 1992 print. This book has not been re-released. These won't last long!

$149 + Postage

Buy Now

Yarns & Photos

We have found in storage the last few boxes of the original 1992 print. This book has not been re-released. These won't last long!

$149 + Postage

Buy Now

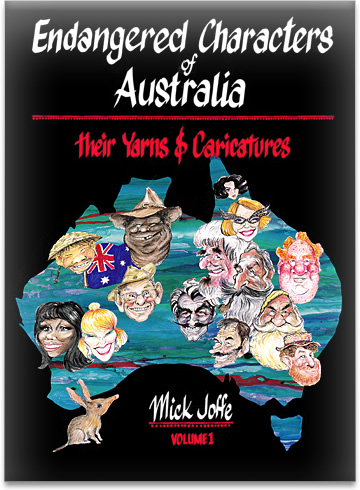

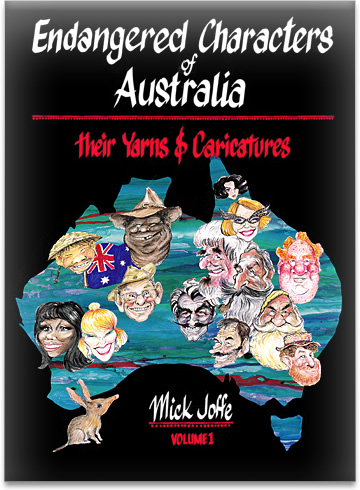

Endandgered Characters of Australia

We have found in storage the last few boxes of the original 1995 print. This book has not been re-released. These won't last long!

$149 + Postage

Buy Now

Endandgered Characters of Australia

We have found in storage the last few boxes of the original 1995 print. This book has not been re-released. These won't last long!

$149 + Postage

Buy Now

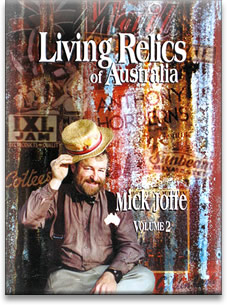

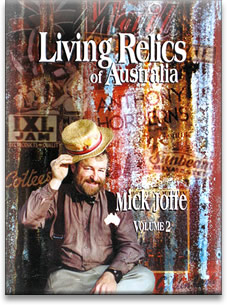

Living Relics of Australia

Living relics contains 25 of our greatest living characters. This coffee table hard-cover book combines the very Australian art of caricature with oral history - the history of drovers, shearers, naturalists, miners, artists, explorers, etc. Their caricature captures them on the outside and their own words capture them on the inside.

Only $29 + Postage

Buy Now

Living Relics of Australia

Living relics contains 25 of our greatest living characters. This coffee table hard-cover book combines the very Australian art of caricature with oral history - the history of drovers, shearers, naturalists, miners, artists, explorers, etc. Their caricature captures them on the outside and their own words capture them on the inside.

Only $29 + Postage

Buy Now

Interviewed: 1997

Published online: Saturday, 13 August 2011

This interview is from Endangered Characters of Australia.

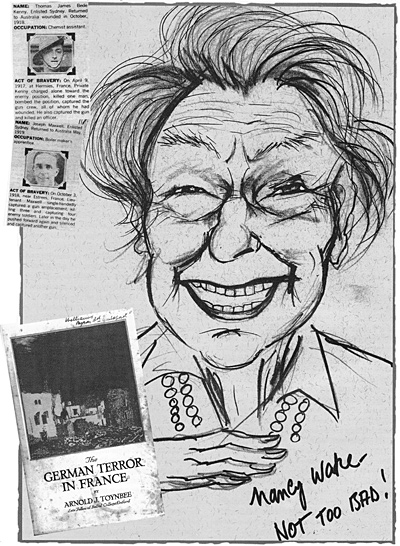

Nancy Wake

30 August 1912 - 7 August 2011

The White Mouse

I came to Australia when I was 20 months old with my father, mother, 2 brothers and 3 sisters. They're all dead now. That was in the days when New Zealand and Australia were all friends and they gave us all an Australian passport, and I went all over Europe with it till the Nazis took it. I've legally got 3 passports, a British, a New Zealand and an Australian one.

When I was in Vienna in 1937/'38 there was a beautiful town square. The Nazis had the Jews on a big wheel going around like a chocolate wheel, maybe a dozen of them, and they were whipping them. I was a journalist and I got the cameraman to take photos but the Germans confiscated the camera. It was too early for them to take us.

People have often asked me how I came to work against the Germans. It was easy. It was in Vienna that I resolved that if I ever had the chance, I would do anything, however big or small, stupid or dangerous, to try and make things more difficult for their rotten party. More than hatred or anger, I felt a deep loathing for the Nazis.

By the Spring of 1934 over 60,000 Germans had left their country but no one wanted to hear their stories of the New Germany. The majority of politicians and their leaders all behaved like ostriches whenever the subject of Hitler was broached. Alas, very soon the world was forced to admit the existence of the new word - GESTAPO - but it was too late and by the time the people took their heads out of the sand, hundreds of thousands of innocent people had been slaughtered.

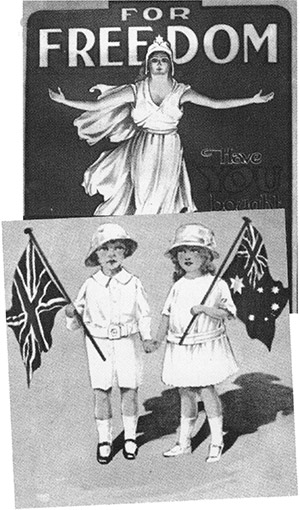

My admiration for these refugees from Germany and Austria grew and I would seek out their company. I have always been a good listener and those years were interesting and informative ones for me. I was able to hear the views of some brilliant men, experienced in the ways of life. We were united by our principles. They accepted me because I too believed in freedom. I was young but I already knew the horrors a totalitarian state could bring, and long before the Second World War was declared, I also understood that a free world can only remain free by defending itself against any form of aggression. I knew too that freedom itself could not be permanent. It has to be defended at all cost, even if by doing so part of our freedom has to be sacrificed. It will always be in danger because, alas, victory is not permanent.

I was in France when war was declared. The Australians from the First World War left a terrific reputation in France. Henri [Nancy's French husband] received his call-up papers and left for an unknown destination in early 1940. I joined a small voluntary ambulance unit, driving an ambulance Henri had provided. As we drove to the north of France we met Belgian refugees streaming down the highways on their way south. The impression I had formed of the Germans years before in Vienna and Berlin did not improve as I watched their aircraft strafing civilians - old women, old men, children, or anything that moved. It was a horrifying sight, especially the bodies of the children.

When Paris fell, I cried for days. My feeling of despair was profound and millions of French people felt even more deeply. Their joie de vivre vanished overnight. They had Germans to the north, Mussolini to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and in the south, the formidable Pyrenees separating France from Spain.

That mini-series on my life with Channel 7 was absolutely atrocious. Not the actors; Noni Hazelhurst and John Waters were wonderful. It was the script; the script was all stupid. We had a big battle in France; our wireless operator lost his life and we lost the link with England. I got a stolen bicycle - I had no permit for it, no identity card, and I had to travel 500 kilometres through German-held territory with no papers, to get a link with England. At night I'd hide in the bushes. When the Germans stopped me, I'd just have a carrot or turnip and I'd explain that I'd just come back from the markets. In the TV series, Noni's basket was full with fresh vegetables!

Silent killing - two experts from Changai police taught us. If a German came at me I'd kick him in the three piece service and chop him in the side of the neck. Most of the time I was decoding. I was in charge of arming the Resistance. We had to train them and show them how to fight and they were magnificent. There were 3,000 of them when we came and they had a recruiting drive and grew to 7,000 Maquis men. We had 27 parachute fields.

Nancy Wake and Phyl Joffe.

Nancy Wake and Phyl Joffe.

The Germans called me the White Mouse; I don't know why. That was from my file in Berlin. There is a theory it's because a white mouse is a sneaky little mouse that slips through and runs through fields. One of my friends was called the White Rabbit.

I started in France with the escape routes, right after Dunkirk. I met them at Marseilles and helped the officers on an escape route through Spain. Do you realise I walked over the Pyrenees 17 times! I couldn't do it now! (Laughter) The last time, I didn't come back; I went on to England.

In the trains with the Germans, I had a good lurk. I smoked and I never had a light and I'd talk to them and if they asked me for a date, I'd say, "Oh, that would be great," but I'd never turn up. I was quite good-looking and looked as if I could be available. Ha, ha, ha, ha. I was friendly, I was polite and was always well dressed and I had a good excuse for travelling. My French was perfect and I had an accent from Provence and the Germans were easier to fool than the French.

By July 1944 there were so many branches of the Resistance, it was difficult to keep track of them. There were left-wingers, red-hot Communists, government officials, civil servants, ex-Vichyites, ex-Milicians, secret army, regular army and dozens more, besides masses of individuals trying to get on the bandwagon. We kept our distance from the would-be politicians, concentrating on arming the Maquisards as efficiently and rapidly as possible.

They attacked the enemy convoys on the road; they intercepted and stole hundreds of wagon-loads of food being transported to Germany; they set up ambushes in the most unlikely places and generally made the existence of the Germans in the area a perilous one. Apart from these activities, they manned the dropping zones at night and, in their spare time, they prepared the explosives needed to destroy the targets we had been assigned.

I had to find new fields where we could organise our air-drops. This was becoming more and more difficult as the Germans were attacking Maquis groups every day in retaliation. I had to shoot my way out of a road block on two occasions and I was extremely fortunate to escape capture. In the latter part of July and during August, 1944 I was travelling continuously. Every night hundreds of containers filled with weapons and explosives were being parachuted on to our fields in anticipation of the Allied landings which ultimately took place in the south of France on 15th August.

The most exciting raid I ever made was an attack on the German headquarters in Montlucon. Tardivat and his men organised this raid from beginning to end. All the weapons and explosives used were hidden in a house near the headquarters, ready to be picked up just after noon when the Germans would be enjoying their pre-lunch drinks. Each one of us had received specific orders. I entered the building by the back door, raced up the stairs, opened the first door along the passage way and threw in my grenades, closed the door and ran like hell back to my car which was ready to make a quick getaway. The headquarters was completely wrecked inside the building, and several dozen Germans did not lunch that day, nor any other day for that matter. The hardest part of the raid was to convince the nearby residents that the Allies had not landed and that they should return immediately to their homes and remain indoors.

In the early hours of the morning of 15th August, the long-awaited invasion of the south of France became a reality. Nearly 300,000 troops, comprised of Americans, British, Canadians and French, disembarked between Toulon and Cannes. The Resistance movements all over France had been anxiously awaiting the landings, as it would mean the beginning of the end for the Germans.

The numerous Maquis groups set about destroying the targets they had been assigned for the second D-Day. I'd brought the plans for these raids from England in a handbag - the bridges, roads, cable lines railways, factories - anything that could be of use to the Germans.

Germans executing Freedom fighters.

Germans executing Freedom fighters.

I fervently believe that the French Resistance played a major role in the liberation of France. They were a permanent thorn in the sides of the Germans, thus preventing them from putting all their strength into fighting the Allies during and after D-Day.

Paris was liberated on 25th August 1944 and the whole country rejoiced. It would be hard to describe the excitement in the air! After defeat and years of humiliation, their beautiful capital was free. The aggressors were now the hunted. The Germans were on the run and the French people were overcome with joy. The collaborators seemed to have vanished into thin air and the crowds in the street went wild with joy. All through the night we were feted wherever we went.

I met De Gaulle after the war - very nice, very austere, very formal. A very loving and devoted husband to his wife, his family and his country. As far as Churchill is concerned, I think he was also wonderful and I loved him. As for that nasty little Mussolini, I spit in his eye.

I was a speaker in Melbourne for Patsy Adam-Smith. Over a thousand women from all over Australia attended. I used to go around and talk at meetings and they'd say, "Have you got an Australian Award?" and when they heard I didn't, they'd be disgusted. I said, "I don't want a medal. I didn't fight for medals; I fought for freedom." The medals I have were given with warmth, with gratitude and with respect. I never said I am the most highly decorated Australian of World War 2 but if it is true, I want to be the most highly decorated Australian without any Australian awards and if they've got medals, they can stick them where the monkey put the nuts. I think it's funny, don't you? The jam is on their face, not mine.

Whole families perished at Gerbeville: La Prele.

Whole families perished at Gerbeville: La Prele.

The Americans gave me the Medal of Freedom; done in Paris in an Officers Club. A magnificent ceremony with Generals. When the French upgraded me to be an Officer of Legion of Honour, I was the only one to be decorated 200 ratings in a helicopter carrier in Sydney Harbour.

They were always asking me in Canberra if I could lend them my medals. I asked John [Nancy's second husband], "What the hell? We have no children. We don't need them." So we agreed to sell them to Sothebys. I had about 10 medals and Sothebys valued them at between 40 and 60,000 dollars. The phone rang and it was Jimmy James, who lost his leg in Vietnam, the president of the RSL in Canberra. He asked me if I would stop the sale. He would give me $50,000 if I'd withdraw them from the sale. He didn't want the medals to be in the wrong hands. I refused; I rang up Sothebys and they said it was very unorthodox. The sale went ahead and I think they sold for $159,000.

I think compassion is very important. To be compassionate about people; to be truthful; to be honest. What do you think? I hope you are married because I deplore all these people living in sin, sometimes 4 or 5 different fathers and on the pension. I think you've a magnificent family with your wife and children. I'll be quite honest, I'm impressed. I mean it and that book ['Endangered Characters of Australia'] is a beautiful addition. I never say anything I don't mean.

I feel very safe in Australia; I feel safe in London and I feel safe in France because throughout my life, in wartime or in peace time, I have always tried to help people if I could.

Nancy in British army uniform, that of the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry.

Nancy in British army uniform, that of the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry.

There had been nothing violent about my nature before the war yet the years would see a great change. The enemy made me tough. I had no pity for them nor did I expect any in return.

I've travelled to Germany many times since the war. It's a lovely country to visit but I keep well away from the older generation of Germans in case I become involved with some ex-Nazi. I will never be able to forget the misery and death they caused to so many millions of innocent people; the savage brutality, the sadism, the unnecessary bloodshed, the slaughter and inhuman acts they performed on other human beings. I am inclined to feel sorry for the young Germans of today, knowing how utterly miserable I would be if I was descended from a Nazi.

Just after the liberation of France, I was dining in the British Officers' Club - previously, German Officers' Club - in Paris. Our waiter, an impatient, discourteous fellow, muttered under his breath, in French, that he preferred the Germans any day to the rotten English. That was too much for me. I followed him into the servery and delivered a few choice words, followed by a mighty punch on the jaw. He fell flat on his back, unconscious. Much later, I was told that the Third Secretary advised the manager and the waiter to forget the whole affair, adding, "Do you know that just a few weeks ago this woman was killing Germans who would make mincemeat out of you two?"

I've been here [Port Macquarie] 8 years. I'm a very retiring person. I don't go looking for publicity but people are coming up to me in the street and saying, "I know who you are." Gee, I can't go round incognito now like I did in occupied France. Ha, ha, ha, ha.

If I can't sleep at night I go back to my memories; I've got so many. I've had such a fantastic life; things always seem to turn out right for me. My mother told me when I was born, a Maori midwife who brought me into the world said, "This little girl will be lucky in her life. She has been born with a veil over her face," and handed me to my mother. When I look back on my life, was it true?

When invited to our carauan, Nancy Wake took each of our four kids and demonstrated her silent killing on them. They were thrilled. A greater character you could not meet. Nancy Wake and Sister Bullwinkel are Australia's most famous wartime women.

Mick Joffe

More Characters

Since the early 1970s, Mick Joffe's passion has been to caricature and record endangered characters of Australia, and the world. As of 2015, the majority of these interviews exist only in manuscript form.

Click here to see the full list of interviews...

Yarns & Photos

We have found in storage the last few boxes of the original 1992 print. This book has not been re-released. These won't last long!

$149 + Postage

Buy Now

Yarns & Photos

We have found in storage the last few boxes of the original 1992 print. This book has not been re-released. These won't last long!

$149 + Postage

Buy Now

Endandgered Characters of Australia

We have found in storage the last few boxes of the original 1995 print. This book has not been re-released. These won't last long!

$149 + Postage

Buy Now

Endandgered Characters of Australia

We have found in storage the last few boxes of the original 1995 print. This book has not been re-released. These won't last long!

$149 + Postage

Buy Now

Living Relics of Australia

Living relics contains 25 of our greatest living characters. This coffee table hard-cover book combines the very Australian art of caricature with oral history - the history of drovers, shearers, naturalists, miners, artists, explorers, etc. Their caricature captures them on the outside and their own words capture them on the inside.

Only $29 + Postage

Buy Now

Living Relics of Australia

Living relics contains 25 of our greatest living characters. This coffee table hard-cover book combines the very Australian art of caricature with oral history - the history of drovers, shearers, naturalists, miners, artists, explorers, etc. Their caricature captures them on the outside and their own words capture them on the inside.

Only $29 + Postage

Buy Now

Caricature of Nancy Wake, by Mick Joffe

Caricature of Nancy Wake, by Mick Joffe

Geoff MackCountry music singer and songwriter

Geoff MackCountry music singer and songwriter Gordon JohnstonA Pitt Town Local Legend and character

Gordon JohnstonA Pitt Town Local Legend and character Rod EmmersonRockhampton’s popular cartoonist

Rod EmmersonRockhampton’s popular cartoonist Laurie Wilson“Laurence of Arcadia”

Laurie Wilson“Laurence of Arcadia” Lindy Chamberlain“A dingo took my baby!”

Lindy Chamberlain“A dingo took my baby!” Fred CostelloSpeared by Aborigines

Fred CostelloSpeared by Aborigines